A spate of blog posts in the past week have focused on issues of academic online civility and community: Kathleen Fitzpatrick‘s “If You Can’t Say Anything Nice” (25 Jan), my response “If You Can’t Hear Anything Nice,” her response “Disagreement,” my response “Behave, Listen Well, and Design for Liberality,” Dan Cohen‘s “The Sidewalk Life of Successful Communities,” Ryan Cordell‘s “Mea Culpa: on Conference Tweeting, Politeness, and Community Building,” Tressie McMillan Cottom‘s “What’s In A Name?“, Lee Bessette‘s “Twitter Controversies,” Roger T. Whitson‘s “Twitter Bully,” etc.

Generally, commentators are focused on the problems of unacceptable or inappropropriate public shaming, disrespectful critique or “quick complaint.” I don’t condone such things, but would like to add the observation that responding to perceived incivility or social inappropriateness too absolutely or zealously has perils of its own. Intellectual inquiry has to steer carefully and self-critically between many pitfalls and dead-ends, including not only incivility but also insularity, like-mindedness, and an unwilllingness to engage with difficult speech or conflicting norms. This is admittedly a difficult project, continually beset by the enclosing aspects of our habits, our cognitive biases, our disciplines and our institutions. But in that regard, academics and intellectuals are, or should be, like Avis: we try harder.

Whenever we see denunciation of rude or uncivil behavior, we might give pause and consider who else, historically, has tended to be so accused? That would probably include, for example, almost all agitators for social change and civil-rights ever; immigrants, the poor, and the working class; religious reformers & dissidents; people from historically disadvantaged groups entering fields and hierarchies formerly closed to them; and many great scientists, authors, inventors & entrepreneurs; and many people we’d now consider to have disabilities or illnesses.

Dealing with people who share our notions of good manners, civility, or disciplinary norm is comparatively easy. The greater proof of principles is to be able to convey them to, or at least maintain them among, those who think and/or behave quite differently.

The ethical mandate to engage opposing views has long been recognized, as in the Enlightenment notion of “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it” (often attributed to Voltaire, actually written by Voltaire biographer Evelyn Beatrice Hall in 1906). Or as Supreme Court Justice William J. Brennan, Jr. wrote in Texas v. Johnson [1989], “if there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment, it is that government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea offensive or disagreeable.”

Community and Heterophily

A theme I notice in many posts about academic civility is the notion of “community,” as what scholars are trying to achieve. Clearly, academia is some kind of community, as are disciplines, universities, departments, scholarly/learned societies, and professional organizations. However, it should be recalled that every assertion of “community” is also, logically, an exclusion — whether consciously or not. For others who don’t share your point of view but may have common interests, it may feel like a statement of incivility or contempt. Woody Guthrie observed that “some people rob you with a fountain pen”; and we might add that some people bully you with silence, or a closed door, or exertion of a “community” that excludes you.

In any case, I think building community is just one dimension of what what scholars or academics do, or should do, to achieve their best work and find public purpose.

Equally important to community is going forth from community; travelling, representing abroad, reporting back; welcoming and hosting strangers, dissidents, and factions. Community is a foothold and haven from which to go forth into otherness; it isn’t the sole or end purpose.

If you consider humanistic academia to be about deep intellectual inquiry, advance, and innovation for the ultimate good of society and mankind, then better metaphors for the overall enterprise might be, cosmopolis, forum, or (dare I neo-liberally say) marketplace of ideas. All of which don’t imply perfect civility or social harmony, but rather diversity and contest.

One term for this is heterophily, “love of the different” — the opposite of homophily, our tendency to associate with like-minded people. Heterophily isn’t so much the opposite of community, but a particular characteristic of people and communities that are highly open to influence and innovation.

Consider the case of AT&T’s Bell Labs, one of the most famous and productive sites in history for scientific/technological invention, source for many key C20th innovations such as the transistor, information theory, the laser, and Unix. I happened to work for many years for a former longtime Bell Labs research scientist, who often recounted its remarkable atmosphere and social dynamics.

Over decades, Bell Labs cultivated an organizational culture in which brilliant and sometimes quite idiosyncratic people were left to pursue their interests in relative freedom and fluid interaction. For example, in the Bell Labs cafeteria, as my colleague described it, friends of widely different disciplines and expertises would regularly put up anyone’s work or topic as fair game for no-holds-barred, rigorous scrutiny by all, from all angles.

Many people, I imagine, would find such an situation uncivil or aggressive, or just wouldn’t naturally gravitate towards a situation of such open heterogeneity and contest of ideas. Yet it was essential in making Bell Labs an extraordinarily innovative and productive environment.

Bell Labs is a well-known case in a much larger body of research demonstrating benefits of heterophily dynamics in organizations and communities. Everett Roger‘s landmark work The Diffusion of Innovation (1962) highlighted diversity in communities as a key factor in predicting adoption of new agricultural techniques.

Mark Granovetter‘s “The Strength of Weak Ties” (1973) showed that job mobility and other social benefits often stem from people’s weak contacts to outside groups, less to links within their own primary “community.” Robert Putnam‘s Bowling Alone (2000) argued that positive social outcomes depend mostly on bridging social capital that connects heterogeneous groups, as opposed to bonding social capital that is primarily within-group.

Incidentally, the paywall journal system may be a significant instrument of parochialism and homophily, because it tends to focus scholars around only the journals & tools to which they have access, and nobody has equal access to a full public sphere. I would suggest that the most pervasive & damaging form of academic incivility is not local and explicit, but global and implicit: disengagement from other disciplines/fields and wider publics; parochial focus on one’s own discipline, field, journals, and career gatekeepers.

The Future: Social Network Analysis and Altmetrics

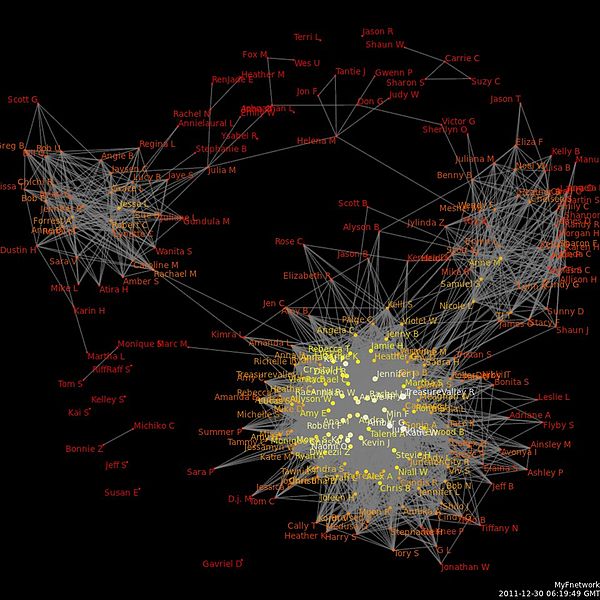

The above considerations intersect in an interesting way, I think, with key academic trends towards Open Access publishing and “altmetrics” which track scholarly impact by means such as social-media activity. New metrics based on online and digital activity may surface patterns of social interaction and dialogue showing homophily or heterophily tendencies, and this could in theory be used to predict and evaluate academic productivity and innovation.

As Altmetrics founder (and coiner of term) Jason Priem observed in 2011, scholarly use of Twitter can potentially reveal “a vast registry of intellectual transactions,” far more detailed and usable than the sparse and slow older signals like citatations.

My hunch and hope is that emerging practices such as Open Access, Social Network Analysis and Altmetrics will tend to give greater acknowledgement to values of heterophily, as compared to existing systems such as disciplinary departments and journals, which may tend to reward homophily. In a more wide-open, fluidly-interlinked, and transparent communications system, divergent and bridging voices can find more doors open to them and more ways to avoid being enclosed by too local a community.

The result, we can hope, will be communities that are not only civil but fluid and adaptive, cohesive but interconnected and Other-engaged — safe to be in, but also safe from which to venture forth.

@rrkennison @deborahatbmc to me not just #OA but discussion patterns, of interest: “Between incivility & insularity” http://t.co/ZSWS7GgTSE

how do you create good online conversations? “Steering between incivility and insularity http://t.co/Abc37B98gx”

how do you create good online conversations? “Steering between incivility and insularity http://t.co/Abc37B98gx”

@mgorbis love your post. I came to US at 10 from UK, dual citizen, similar experiences. Related, on heterophily: http://t.co/VVswmvbrly

@mrgunn @MikeTaylor @arusbridger “’civil’ or ‘polite’ may serve similar purpose”: quite. Cf “Incivility, Insularity” http://t.co/Abc37B98gx

@MikeTaylor @pannapacker quite. I discuss this in “Steering between incivility and insularity” http://t.co/Abc37B98gx