published November 13 on HASTAC (Humanities, Arts, Science and Technology Advanced Collaboratory).

I review a Humanities academic’s case against Open Access publishing, and find that the arguments are unconvincing, status-quo-bound, and ultimately limiting.

An American PhD candidate in Sociology at Trinity College, Cambridge, Casey Brienza, recently published an article in Publishing Research Quarterly, entitled “Opening the Wrong Gate? The Academic Spring and Scholarly Publishing in the Humanities and Social Sciences” (Sept 2012, Vol 28, Issue 3, pp 159-171).

To summarize Brienza’s article, she gives a description of the so-called “academic spring” in 2012, a movement in favor of Open Access scholarly publishing, as beginning with mathematicians’ boycott of publisher Elsevier and subsequently spreading to scholars in the humanities and social sciences (HSS),

She then argues that HSS fields are not equivalent in business practices or preferred publication venues to the STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) in which Elsevier primarily publishes.

She identifies the above-defined movement as having two moral or ideological objectives/rationales:

- liberation from immoral capitalist exploitation of academic labor and

- increased access to and engagement with scholarly knowledge

and then argues that alternatives to the status quo such as Open Access, do not necessarily support those principles, for the following reasons:

- HSS scholars will only harm their careers by steering away from high-status non-OA publications. (Yale librarian Susan Gibbons’ argument thus has been widely cited elsewhere).

- Digital publication doesn’t actually make materials available to everybody.

- Open Access may “profoundly transform the nature of academic research itself” and may cause existing forms of scholarly production to cease, e.g. the monograph.

Asked about the choice to publish a piece about Open Access (free to access) publishing in a paid-subscription journal that charges $39.95 for individual access to the article, Brienza commented on her Livejournal page.

the argument I’m making rests in large part upon a correct understanding of how publishing works, and most academics don’t really understand the publishing industry. So, placing it in a journal dedicated to publishing research is a way to directly signal to them that I’m not just bullshitting about the basics. Of the two publishing research journals I know of, this one has a wider subscription base. And besides, the article is mostly addressed to those people who would have institutional means to get access, anyway.

Because I have a strong personal and professional interest in humanities & social science (HSS) and its publishing, I disregarded this disinvitation and decided I would brave disciplinary and practical boundaries to read the article, even though I’m not in the intended audience.

Kafka’s “Before the Law”, Orson Welles’ version: “by the guards permission, the man sits down by the side of the door, and there he waits”

In the spirit of public disclosure, initially I contacted Brienza to see if any version or preprint or other presentation of the arguments was available, and she did not respond to repeated inquiries. Nor did it work to observe that her advisor, John B. Thompson, had built his scholarly work upon extensive discussions with people in the publishing industry, which seems like a sensible idea when writing about the publishing industry, and I coming from said industry might even try to be helpful on the matter, were I to be granted admission to the conversation.

As I paced forlornly outside the walls, I also noted that I’m a British (as well as U.S.) citizen, and my family has paid goodly sums into the tax system that is the primary funder of the U.K. public university she attends, and the scholarships which paid for her, an overseas student, to be there. (which I am happy for the country to do, by the way, but which I view as a public expenditure for public benefit, like any other). But, no response.

I felt like the man from the countryside in Kafka’s “Before the Law”:

Before the Law stands a doorkeeper on guard. To this doorkeeper there comes a man from the country and prays for admittance to the Law. But the doorkeeper says that he cannot grant admittance at the moment. The man thinks it over and then asks if he will be allowed in later. “It is possible,” says the doorkeeper, “but not at the moment.” Since the gate stands open, as usual, and the doorkeeper steps to one side, the man stoops to peer through the gateway into the interior. Observing that, the doorkeeper laughs and says: “If you are so drawn to it, just try to go in despite my veto. But take note: I am powerful. And I am only the least of the doorkeepers. From hall to hall there is one doorkeeper after another, each more powerful than the last. The third doorkeeper is already so terrible that even I cannot bear to look at him.”

These are difficulties the man from the country has not expected; the Law, he thinks, should surely be accessible at all times and to everyone, but as he now takes a closer look at the doorkeeper…he decides that it is better to wait until he gets permission to enter.”

Well, actually I thought about for a bit and then decided that uncollegiality and guardedness regarding an article about open-access publishing was altogether too much amusing, ironic fun to leave in peace, so I walked right through the first gate, at least, and got a copy of the article to read.

So here are my thoughts, my day’s bit of thinking in public, which you are quite free to take or leave. (attention, hiring and tenure committees! Completely outside-of-the-fold public impact and input here). Since the original article or arguments are not publicly available, by Brienza’s choice, they will be inaccessible to most readers here, and so to some extent I unfortunately have to speak for her in describing what she says, whereas I’d prefer for anyone to be able to read her original presentation.

First of all, the article’s argumentation and scholarly level, despite being in what she describes as a leading peer-reviewed journal on publishing, I would characterize as, uncompelling.

She starts with a history of the Open Access movement in scholarly publishing, which she presents as beginning with Tim Gower’s Elsevier boycott starting in 2012, that is not far from caricature. Anyone familiar with the movement — a critical peer-reviewer, perhaps? — might immediately observe that OA explicitly goes back at least to the Budapest Open Access Initiative declaration in 2001, with clear antecedents in many fields going back decades.

OA is hardly the recently launched, self-righteous moral/ideological “bandwagon” Brienza describes, but has been quite thoroughly and broadly examined and endorsed over the last 15 years by a huge range of stakeholders ranging from public funding agencies (Wellcome Trust, NIH, Max Planck Institute, etc.), major universities, scholars across all disciplines, students, medical patients and professionals, and a large part of the publishing world, including many major commercial publishers such as Sage and her own publisher, Springer; and even by openly capitalist scholarly-communication startups like PeerJ. See Wikipedia for a detailed discussion and history of the movement.

In one of many straw-man arguments, Brienza suggests that “too many scholars seem to assume that if an article or a book is ‘open access,’ it must necessarily then be available to all people equally and therefore in perfect alignment with the greater public good.” Who argues this? Even if they had, it’s fairly obvious that an Open Access publishing model generally make material more available to diverse publics — working stiffs and country bumpkins like me, for example. You might attempt a case that, say, closed subscription models incent production of goods which can in some ways be redistributed to other publics, e.g. by developing-world access programs; but it’s a difficult case, and she doesn’t attempt or even cite anything such.

Even before one gets to the personal-interest revelation at the end, about how her mother was a decades-long employee of the corporate, subscription-publishing colossus Reed Elsevier being defended in the article — even before, one is taken aback by the apparent pro-corporate partisanship. For example, we learn that “corporate publishers of journals and books have vastly increased the carrying capacity of the academic publishing enterprise, and continue to do so, supporting career advancement for a greater number of scholars than ever before in history as well as the accelerated production of new knowledge they fuel.”

That’s a broad and interesting claim, but hardly the type one can usefully make without argument, evidence, or citation. Making it in a corporate-published, Springer journal is not really credibility-enhancing, either. One might reasonably ask how this beneficient corporate publishing system really supports or fuels academics’ careers, since it has long been based on large-scale uncompensated labor by academic authors and peer-reviewers, and appropriation of their copyrights in the work. Or, you might reasonably wonder why these publishers have overseen skyrocketing journal prices over the last 20 years, with no obvious cost rationale, while recording profit margins of up to 35%, unheard of in most industries; even as organizations such as ArXiv have demonstrated the ability to run scholarly-article systems at a tiny fraction of the commercial publisher’s prices.

While she reifies the incumbent journal-industrial complex, she “struggle[s] to imagine how an enterprise of this organizational magnitude could continue, never mind be reconstituted whole cloth, on a volunteer-only basis.” Of course, this is a straw-man proposal that nobody really suggests, and it seems without cognizance of the wide range of proposed and operating new scholarly communication systems, e.g. HASTAC in the humanities, SSRN (Social Science Research Network), or ArXiv, which dramatically diverge from commercial closed-access models but have been quite successful.

But wait, there is bigger game afoot than just, publishing. The problem is really the whole web, the universe, and everything: “The web’s…apparent egalitarianism is in fact a reinstantiation of the bad, old structures of domination.” Again, an intriguing argument, had we a bit more world enough and time; if largely at odds most people’s experience and analysis. We might look at various critical examiners of Internet culture/industry/policy such as Lawrence Lessig, Jonathan Zittrain, Jaron Lanier, or Evgeny Morozov; but as given here by Brienza, it isn’t a scholarly argument, or rigorous or supported by anything; it’s not much more than off-the-cuff editorializing, which I could get more easily on many an open-access street-corner or twitter feed. Likewise, “academics may be running headlong into unintended, even tragic, consequences.” Such as? and why? I guess we should just be very worried.

Finally, Brienza addresses what she considers the problematic idea that we might “profoundly transform the nature of academic research itself.” This, she says, is not likely to be, because, well, it’s not likely to be:

“The sociology of cultural production teaches that that form in which cultural content takes is shaped and constrained by the social structures within which it was produced. Why should scholarly articles and books be any different?”

Now what is the argument here? I see little more than an assertion of conservation — that there are observable social structures and processes, so they will stay that way. But how could anyone look at the last few centuries of scholarly endeavor and not see radical changes over time? For example, as Kathleen Fitzpatrick observes, peer review and tenure in our senses hardly existed until the early to mid-20th century.

Speaking of a status-quo view, I was reminded of my reaction to the work of Brienza’s advisor, John D. Thompson, Books in the Digital Age (2005). This book surveys U.S. & U.K. academic monograph publishing based on a sociological “field of production” framework mainly adopted (he says) from Pierre Bourdieu. He proposes that a given “field”, such as what he’s delimited, is best understood as a system of self-reinforcing logic and dynamics. He argues that the e-book revolution is totally exaggerated, and the real revolution is elsewhere, e.g. with consolidation of publishing firms into conglomerates, and the publishing cultural field is largely reproducing itself across this terrain.

Now, I wouldn’t claim to be an expert on the sociology of culture, but I have been bumping around various corners of academia, publishing, and the Internet for 20 years or so, with my eyes not totally shut. Coming from this empirical vagabondage plus the occasional dab of related reading, my sense was that Thompson’s argument seemed rather rigid and not highly descriptive of the dynamic publishing world I’ve encountered. While Thompson largely dismisses e-books as overblown, just seven years after the book was published, the e-books sector has exploded to a level of uptake and revenues beyond the highest initial projections, and book publishing is being radically transformed by players such as Amazon and Apple that were essentially outside Thompson’s “field.”

Admittedly, I may be one of the frothing barbarians at the Western gate — see for example Ken Auletta’s “Get Rich U.” on the Silicon Valley / Stanford nexus — but from out here on the fringe, to hear an academic at 800-year-old Cambridge argue that a media industry is some kind of fixed field sounds a bit.. fixed. As in, not especially engaged with the spirit of reinvention and innovation that can turn industries or societies upside down, which does actually happen now and then. (See: Printing Press; Railroad; Automobile; Internet; Personal Computer; E-Book, etc.).

The point is, both Thompson’s Books in the Digital Age and Casey Brienza’s “Opening the Wrong Gate?” strike me as burdened with a sense of inevitability or prior sympathy for an existing order — and seemingly chilled by the ‘winds of freedom blowing.’

Brienza’s essay leads to this not-quite-rousing call to action, “if HSS researchers are concerned about serving the public interest…they must do the work themselves after they have become well-published.” It’s a bit hard to say what this means, but in explanation she links to a 2011 post on LSE Impact of Social Sciences blog where she said,

“Nobody outside of the profession reads scholarly books and journal articles…Your book will not effect change on its own, but if you wave it around high enough and long enough you might be given a soapbox relevant to your research topic.”

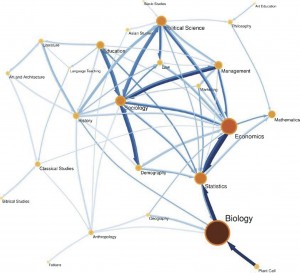

We talk, but it’s complicated: network analysis of citations between disciplines in JSTOR repository, by Bergstrom et al, 2011

Really? we should support a giant apparatus of research, article and book writing and publishing, even if in itself has no public meaningfulness or impact, just so academics can arrange the seats at their table and establish careers; from which they might try to later perhaps have some impact if there’s some time and energy left over?

If that’s your case for why to get public or tuition-payer or any other type of support, and that’s your level of regard for your own work, field, and publics, I fear you have some rather rough times ahead. There are a lot of other ways people can spend and legislate money, and produce and demonstrate value; and I know many passionate, committed teachers, scholars, and innovators who aren’t cynically centered on their own career advancement, who do believe in their work and wish to share it for public benefit — and to aid their own learning and work, I might add. Because it’s good to talk to diverse other people who know things — that’s called research, and conviviality.

Those more mission-spirited academics are whom, frankly, I would rather entrust with my learning or my children’s, or my reading time or tax dollars, and in my view it’s a poor long-term strategy for humanities academics or anybody to wave around self-described irrelevancies or esoterica, and expect this to earn support and a living.

Overall Brienza’s article reads to me like the contortions of an a priori point of view trying to evade the scrutiny of open argument, and haunted by its own shame of disciplinary marginality. It’s truly unfortunate if the state of HSS academia is so embattled and hardscrabble as to lead to this, but I think that in such a climate, we should be looking for how to open new gateways to relevance, not throwing principles aside and self-privatizing.

I actually believe deeply in the humanities’ broad relevance, and look for how to evolve practices that will encourage, highlight, and champion it. Some outstanding examples of that, for me, include the following (the first two of which were also mentioned in Casey Brienza’s article):

- HASTAC‘s peer network and platform for publishing and events

- MediaCommons‘ explorations of open peer review and participatory publishing models

- PressForward at George Mason University, developing new ways to catalyze, curate, and re-publish online scholarly discussion

- the Altmetrics movement, helping to open a space for HSS academics to articulate unique values and practices that should be recognized as “output” for purposes of hiring & promotion, grant funding, etc.

As many have realized, we don’t have to, and aren’t necessarily well-advised to, just keep knocking on the door of old, exclusionary institutions. Or as Virginia Woolf wrote at the start of A Room of One’s Own, recollecting being denied entrance to Wren Library at Casey Brienza’s own Trinity College, Cambridge in the 1920s:

“Venerable and calm, with all its treasures safe locked within its breast, it sleeps complacently and will, so far as I am concerned, so sleep for ever. Never will I wake those echoes, never will I ask for that hospitality again..”

Unlike the man in Kafka’s “Before the Law,” Woolf didn’t let the gatekeeper determine the way, but rather looked for new directions. So, I believe, the humanities today have a future in new directions and open paths.