1. Introduction: Objects, and being in the world

People sometimes say to me, you’re quite particular about… forks, say. Or notebooks, or wrapping paper, or of course, pens. I’d like to think they mean, say, tasteful, or perceptive, but I’ve learned, that’s generally not it. No, there’s some suspicion about appreciation and attentiveness to objects, beyond a point. Why is that?

We’re also told that objects aren’t the path to happiness, may often hinder it: as for example in the New York Times piece, “But Will It Make You Happy?” (August 7, 2010) that originally prompted me to write about this. The author notes, in summary, “people are happier when they spend money on experiences instead of material objects.” It cites the notion in psychology of “hedonic adaptation,” meaning that changes in circumstance, such as a new possession, tend to quickly stop affecting you.

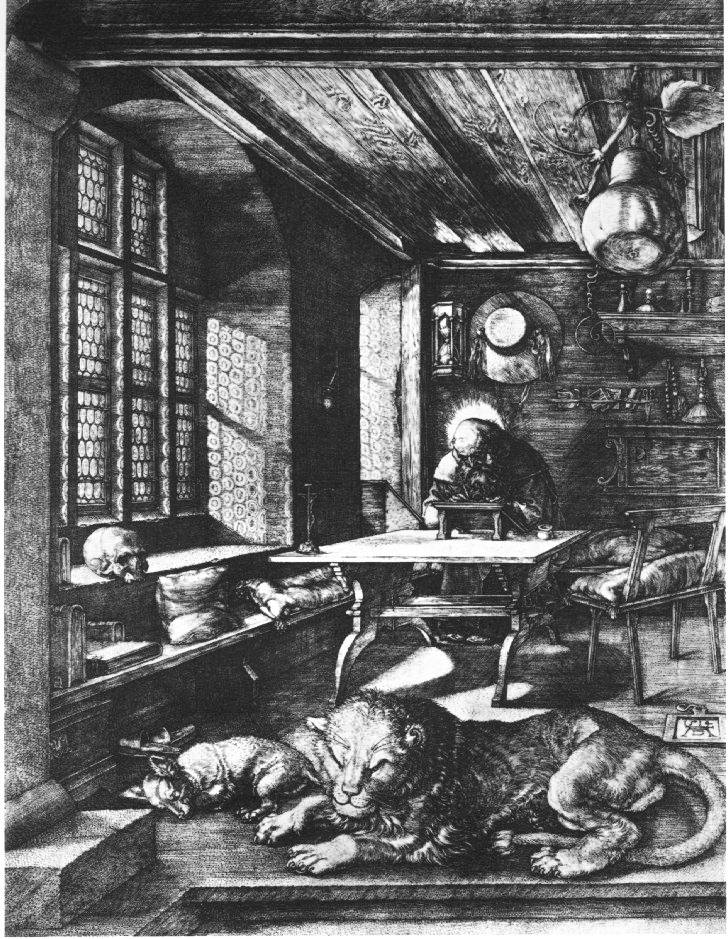

However, conceding the point that our happiness may relate more to having strong relationships and good experiences — for some — I’d like to see the care for objects as something equally basic and valid, deep in our homo faber (tool-maker) natures. More particularly, I think of it in the tradition of moral/social/aesthetic reactions to industrialization: such as the 19th-century Arts and Crafts movement, and its descendent Modernism and latter-day movements (“Maker,” etc.).

In this Arts and Crafts vision, our lives are importantly, meaningfully, and continuously influenced by all parts of their material surroundings, including furniture, textiles, printed matter, implements, tools, and vehicles. “Vom Sofakissen zum Städtebau” (from sofa cushions to city-building) was the slogan of the Deutsche Werkbund, the German state-sponsored design trade association founded in 1907, out of which the Bauhaus school of design grew. Objects, in this tradition, aren’t lowly things, trappings of our lower natures; they are necessary instruments by which we can live richly, spiritually, and humanly.

Consider,by contrast, the NY Times article’s framing:

“One major finding is that spending money for an experience — concert tickets, French lessons, sushi-rolling classes, a hotel room in Monaco — produces longer-lasting satisfaction than spending money on plain old stuff.”

I’d say, well maybe that’s because the stuff you’ve been buying has been plain and old, versus your fancy-pants, haute-couture French and sushi classes and Monaco hotels. How about the pleasure and deep meaning of being in well-made environments well suited to you, using well-made goods and tools?

As Web commentator & designer Jason Kottke remarked in “Upgrade Yourself” (10 Dec, 2008):

“My wife and I are ardent upgraders. I rarely buy anything anymore but the things I do buy are usually better versions of things I already have. As things break or wear out, we’ve been replacing them with items that are nicer to use/wear/whatever and will last a whole lot longer than the cheaper stuff”; “buying nice products that you’ll use for several years/decades is both a financial investment and an investment in your personal well-being,”

If you go through Kottke’s list, you notice that most of his objects are in fact closely related to basic experiences, particularly cooking, eating, and sleeping. See also the nice Metafilter.com thread from 09 Dec 2008: “Upgrade Me,” which discusses the question “Can you suggest some replacements for standard, everyday household items that are far superior in terms of usefulness, luxuriousness and quality?”

In fact, the line between object and experience is quite blurred: is a vase, or a vase of flowers, an object or an experience? It depends what you do.

So, in defense of my own attachments — or lack of attachments, depending on how you look at it — I thought I’d survey some key objects in my life, their greatness or at least great aptness, starting from those physically closest to me and moving outwards. I will consider the question: useless, plain old stuff? Or beautiful augmentations of one’s life, the finding of right connection to the world? Possibly, a mixture.

I’ll consider this matter in a series of posts, examining all types of objects. If this catalog of my paraphernalia may seem inward-looking, well, as Thoreau said, I should not talk so much about my stuff if there were any other stuff that I knew as well. On the other hand there is Montaigne, retreating from professional life, at the same age as me in 1571, to his estate’s tower library to focus entirely on what became the Essais, who said, “These are my my fancies, in which I make no attempt to convey information about things, only about myself.” (“On Books“).

In the next episode: a disquisition on Pens.

.

new post: “The objects in my life: ‘useless stuff’ vs perfect things,” and personal archaeology. http://t.co/fc6gt4hED2

on self-archaeology: “The objects in my life: ‘useless stuff’ vs perfect things” http://t.co/fc6gt4hED2 (new post)

RT @tmccormick: on self-archaeology: “The objects in my life: ‘useless stuff’ vs perfect things” http://t.co/fc6gt4hED2 (new post)

RT @tmccormick: on self-archaeology: “The objects in my life: ‘useless stuff’ vs perfect things” http://t.co/fc6gt4hED2 (new post)

Pingback: The objects in my life, Part 2: Better engagement through pens | Tim McCormick

Hmm, this was quite an interesting piece. I think the objects that preoccupy most people are not only of dubious or low quality but important to them only because of a value the objects have been assigned by marketers and their possessors desire for status or to fit in with others by owning them. If I could wave a magic wand, what I’d want to see is all of us having access to many more beautiful everyday products that are made by craftpeople or small outfits and made to last (versus the obsolescence designed into so much of what we buy now). I would also want people to detach in the sense that they didn’t derive a sense of worth or standing from the objects they owned and reserved that place in their lives for some self-measurement of their personal ethics and how they are in the world. Re objects versus experiences — I think that this is a false dichotomy, since I think you may admit that the pens and books you love create positive experiences for you just as buying a place at a retreat might for someone else. What concerns me, too, in what you’ve written is elitism. I try my hardest not to be a materialist, which for me doesn’t mean that I don’t have favorite objects. It does, however, mean that the ownership of these “things” doesn’t elevate me, in my own eyes above anyone else. So, if I have a fountain pen, it doesn’t make me more shrewd or discerning than someone with a Bic — though on a personal level, the beauty of the fountain pen and the writing experience it produces may make me extremely happy. Again, I’d like to see beautiful objects like that pen accessible to many more people — also, too because a sustainable world demands an end to disposable e products — that the possession of beauty wasn’t such a rarefied experience and that the objects we love aren’t stand-ins for or indicators of self-worth, status and identity.

> the objects that preoccupy most people are not only of dubious or low

> quality but important to them only because of a value the objects have

> been assigned by marketers and their possessors desire for status

I agree. This is central to the ideas of William Morris, the Arts and Crafts Movement, and Modernists too. While the A&C response was generally to turn toward pre-industrial craft tradition, Modernists like the Deutsche Werkbund leaders believed in a union of the old craft quality/fitness with new technology and mass production to make such quality available to all. You might say that’s partly worked, in that a discerning consumer *can* get many very high-quality, well-designed things inexpensively, and in some places like Japan and Denmark there is high general level of design quality for all.

On elitism, I tend to think it’s mostly orthogonal to object attachment. People can be elitist about anything — their credentials, their religiosity, the correctness of their speech, their authenticity, etc. I would suggest that an element of Puritanism or religious asceticism lurks in many people’s disavowal of object attachments, which may lead people to unfortunately disdain or overlook the spiritual value of and human need for well-made/well-fit objects and environs, and associate objects only with consumerism or status-marking.

Even consumerism may have its cultured defenders. Some would argue that consumer culture actually offers a relatively open multiplicity and heteroglossia of ways to express identity and status, as compared to say traditional feudal, military, or agricultural societies, or even in some ways highly competitive, education-oriented societies like present-day China or South Korea. In my case, almost all the objects I most appreciate and write about are private, functional, and fairly inexpensive, so it seems their value and meaning to me is mainly about fitness and pleasure in use, little to do with signaling status to others or exerting elitism. Some of my favorite and most appreciated objects are total mass-production and non-status — like my loved Uni-ball pens, Hema flatware, standard bar pint glasses, etc. — and may even be recovered from trash, or industrial detritus, that most people would think inappropriate or distasteful to keep on hand.

On pens, I wonder if you read my follow-up post, “” (https://tjm.org/2013/09/02/the-objects-in-my-life-part-2-better-engagement-through-pens/)? I didn’t get around to linking to it from this post yet.

Pens are an interesting case (obviously, to me), because while fountain pens have an association of luxury and status, especially to most North Americans, in much of the world they’re mainly a student pen; for that reason, there are loads of fountain pens, including most of my collection, that are nearly as cheap as the leading new-tech pens like rollerballs and gels. If you refill them, they may well work out cheaper than the usually disposable new-style pens, and this greater economy and ecological quality is a important attraction for many FP users.

Looking at it economically, the relative cost of high-quality objects has long been plummeting. In the US today, most people spend most of their money on housing, then transportation to get themselves and their kids around from all those big and spread-apart houses; then healthcare, then entertainment and telecom, then gambling and education, then the global military-security imperium. Top-quality, even artisan home objects such as I’m celebrating can be had for an almost insignificant fraction of the above costs, especially if they’re permanent objects kept for decades. The cost of it all, in my case, is less than what I save on monthly bills by my low-cost telecom lifehacks.

So from that perspective, people may be historically conditioned to under-seek and under-appreciate high-quality craft, because such items have long been associated with unreachable luxury and higher classes. They get bamboozled by the “luxury” industries eager to fill that void, who are often peddling ersatz quality signifiers rather than real quality or craft. But I think the excesses of luxury/consumerist culture, or aversion to elitism, or ascetic impulse, shouldn’t keep us from embracing and appreciating the true richness of objects.