reflections on academics in public, “public sociology” vs. professional sociology, and Jack Mill’s “Three Differences Between an Academic and an Intellectual.“

I. Background

II. The Cyborgology post and I

III. on Public vs. Professional Sociology, & Intellectual vs. Academic

I. Background:

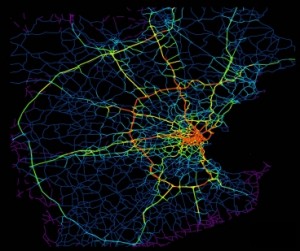

The New York Times ran a story on Dec 22, “The Learning Curve of Smart Parking” by SJSU professor & writer Randall Stross. It describes new systems to detect and communicate parking-space availability to individuals and authorities, and potentially dynamically alter pricing or monitor payment compliance.

Sociology PhD student Nathan Jurgenson wrote a post in reply, “‘Smart Parking’ and the Robert Moses Mistake,” on a blog he co-edits, Cyborgology, which is part of The Society Pages, a public social-sciences project headquartered in the Sociology department at the University of Minnesota.

According to their About page, “The Society Pages’ mission is to bring measured social science to broader public visibility and influence.” The editors-in-chief of The Society Pages are Doug Hartmann & Chris Uggen, both Professors of Sociology at Minnesota, and previously the co-editors of Contexts magazine, a public-oriented quarterly periodical of the American Sociological Association, the primary U.S. scholarly society in sociology.

II. The Cyborgology post & my replies

Jurgenson’s post argues that the smart-parking approaches described by Stross make the same “logical error” as did Robert Moses and other highway-builders, in thinking that building more freeway capacity would solve congestion, which may be untrue if it just incents more traffic.

.

I responded:

Tim McCormick 4:45 am on January 2, 2013 # |

> The logic that more parking information will lead to easier

> parking and less traffic congestion only holds, at best, if the

> number of cars looking for parking stays the same.

No, because better parking information can direct drivers where and when to go. Many studies have shown that a large part of all urban congestion is caused by searching for parking, which could be largely removed by signaling. See for example Donald Shoup, “Cruising for Parking” http://shoup.bol.ucla.edu/CruisingForParkingAccess.pdf.

Shoup’s “The High Cost of Free Parking” is the standard work on dynamic pricing, and presents an exhaustive theoretical and empirical case for why this approach can improve the environment for not only drivers but other parties such as pedestrians, bicyclists, transit, and local residents/businesses.

In addition, recent research [from MIT / Berkeley / Austrian Institute of Techology etc team] suggests that canceling or delaying just 1% of vehicle trips can reduce traffic by 18%, if the right trips are targeted.

So better information, to induce rational behavior change, can dramatically reduce congestion and make parking easier.

> providing an interface of all the unoccupied parking spaces will

> undoubtedly encourage more people to attempt to find parking.

This doesn’t follow. Currently, with poor information, many people make trips in order to look for parking; with good information, many would not make the trip.

In any case, the goal in this case is to reduce congestion and make parking easier, not to reduce the number of people trying to find parking, or driving at all. If reducing number of trips or amount of parking is set as a goal, this can be managed more rationally by limiting supply or raising cost of the parking, rather than restricting information about availability.

.

nathanjurgenson 1:40 pm on January 2, 2013 | # |

okay, but this is mostly restating the theory that i am arguing against in the post.

“the goal in this case is to reduce congestion and make parking easier, not to reduce the number of people trying to find parking”

who is making that argument?

.

Tim McCormick 5:39 pm on January 2, 2013 | # | Reply

Your argument is that smart parking and dynamic pricing would not reduce congestion, based on a historical analogy with part of Robert Mose’s program, coming from a cultural sociology point of view.

I’m just pointing out, and pointing you to, a large and long-running body of theoretical and empirical work by urban studies/transportation experts like Donald Shoup and MIT & Berkeley’s urban studies/transportation departments, that reaches the opposite conclusion to yours.

As you say about writers needing to understand how Internet tools/practices actually work [“the media’s smug tech ignorance“, Dec 31 post] I’m suggesting that writers on say smart-parking / dynamic pricing should try to engage with strong evidence about how it actually works.

If strong arguments and evidence are disregarded, and arguments made based just on what one’s own field or personal interests foreground, then the discussion can easily become disengaged and ineffectual. For example, people I know who are involved in parking or urban planning or transportation now are, in my estimation, not very likely to be influenced by a loose historical analogy from Moses’ NY, vs. recent and current studies of actual smart-parking and dynamic pricing/routing systems.

I think cultural/critical sociology, as in Gans’ and Burawoy’s “public sociology,” can be valuable, and there are many social areas it might illuminate and shape, but its prospects are better the more it’s other- and evidence-engaged. If not, it risks being dismissed as merely creative writing, as those of quantitative/instrumental persuasions are inclined to do.

>> “the goal in this case is to reduce congestion”

> who is making that argument?

Shoup, SF Park, Randall Stross, the recent Urban Parking Salon at SPUR attended by Shoup & SF Park, the MIT/Berkeley/etc research group cited, and the subjects of Stross’ article summarized as “Cities are marketing the programs as experiments in using demand-based pricing to reduce traffic congestion.”

III. Afterword: on Public vs. Professional Sociology, & Intellectual vs. Academic

Former president of the American Sociological Association, Michael Burawoy, advocated for and distinguished “public” vs. professional sociology, building on the term introduced by Herbert Gans’ 1988 address as ASA President:

Public Sociology endeavors to bring sociology into dialogue with audiences beyond the academy, an open dialogue in which both sides deepen their understanding of public issues. But what is its relation to the rest of sociology? It is the opposite of Professional Sociology – a scientific sociology created by and for sociologists – inspired by public sociology but, equally, without which public sociology would not exist. The relation between professional and public sociology is, thus, one of antagonistic interdependence.

In this view, public and professional manifestations of sociology — or by extension, other academic fields — may be not just various modes or faces, but sub-institutions, activities, dispositions in opposition.

“The Lonely Crowd”, 1950, a classic of “public sociology” that proposed three main character types: tradition-directed, inner-directed, and other-directed

In part this, of course, restates in a more rigorous way the commonplace notion of “ivory tower,” or the usage of “academic” to mean separated from and irrelevant to a real-world issue.

However, an intriguing further possibility is that the public and professional notions of academic work align to different character dispositions. Therefore, “professional” practices, and the personality dispositions more aligned with or produced by them, may work against “public” academic modes.

This point is elegantly explored in Jack Mile’s 1999 essay, “Three Differences Between an Academic and an Intellectual: What Happens to the Liberal Arts When They Are Kicked Off Campus?” He considers the incentives, working conditions, and career paths of professional academics, and observes that all are primarily — and more or less necessarily — centered on specialization, channeling of general interest into discipline-authorized topics and approaches, and deference to the views of the hierarchy which the aspiring academic aspires to join. He says this is valid and productive, but usually productive of something other than an engaged, true public intellectual.

a specialist is someone who knows more and more about less and less, a generalist is unapologetically someone who knows less and less about more and more. Both forms of knowledge are genuine and legitimate. Someone who acquires a great deal of knowledge about one field grows in knowledge, but so does someone who acquires a little knowledge about many fields. Knowing more and more about less and less tends to breed confidence. Knowing less and less about more and more tends to breed humility. Popularization [i.e. popular writing by academics], which certainly has its place, conveys the specialist’s confidence but also his or her isolation. [Generalist writing] conveys the generalist’s diffidence but also his or her connectedness and openness to further connections… this is the core difference between the academic and the intellectual in action.

Mills goes on to observe that “most public intellectuals would be more accurately called public academics; for…they retain their academic appointments and, for much of their professional life, their academic constituency.”

In fact, this is the situation with the Cyborgology blog, The Society Pages, and Contexts magazine: they are projects run by and contributed to by people in academic career paths. I should say, I admire and applaud The Society Pages, and its editors/contributors, as an innovative and useful project, generally just the type of new scholarly communication I look to support and build. But from my humble position of know-little generalist — that is to say, someone with little to no chance of being hired by them — I see some value in examining it critically.

For example, to apply a bit of the old deconstructionist close-reading, I note The Society Pages’ mission statement:

The Society Pages’ mission is to bring measured social science to broader public visibility and influence.

Seems straightforward enough. Yet note that it expresses a dissemination from discipline to public, rather than an engagement between them. Presumably, “measured social science” is not what public lag-abouts and workers in the coal-mines like me are up to our spare time, but what professional social scientists do. The truth, the work, the core, evidently happens inside the discipline, non-publicly, to then be brought to “visibility” outside, for “influence” over the public.

By contrast, if we revisit former Michael Burawoy’s conception of “public sociology” we see it is symmetrical engagement:

an open dialogue in which both sides deepen their understanding of public issues.

Which evokes, incidentally, a number of concepts in political/civic communication — symmetric agency, communicative rationality, deliberative democracy, even the Dale Carnegie / Stephen Covey notion of effective communication by “seek first to understand, then be understood.” For which, together, I suggest the term “civil reflection.”

Not surprisingly, a project run by professional sociologists reveals the language and orientation of professional sociology; even as it espouses a certain form of public sociology. Likewise, considering the context and professional affiliations/incentives, it’s understandable that an aspiring sociologist writing about, say, “smart parking” might be less concerned to engage with experts and key works in the fields of parking, transportation, & urban studies, and more to engage with other sociologists.

So What? and How Might We?

All of this bears upon some much larger contemporary debates in academia: the moves towards “altmetrics” and evaluating academic work for public impact well beyond the traditional, discipline-centered metrics such as citations in high Impact Factor journals. Guilds will always have their own rules and rewards. If you want practitioners to truly engage with & serve broader publics, you need structures and incentives that serve this purpose: for example, altmetrics showing substantive impact specifically outside an academic’s discipline.

Also, we may need to better recognize that public and professional academia may be inherently in tension, and that public intellectuals don’t necessarily come from or belong in academia. Or even, by Christensen’s theory of disruptive innovation, that the transformative figures will come from outside of the current cultural “market” entirely — “intellectual entrepreneurs,” say, analogous to moral entrepreneurs, or some new type of engineers of human souls. To be open to this and all possibilities, we have to, as Evgeny Morozov says, look around: engage others, and follow, as Jack Mill said, not so much the specialist’s authority but “the generalist’s..connectedness and openness to further connections.”

nope, my post wasn\’t intended for professional gain or to speak to other professional sociologists. instead, it was intended for and ultimately sparked really nice conversation with people in other disciplines and non-academics (certainly part of the \”public\”). that\’s why i wrote it, to converse with others, especially outside of my professional circles. i assume it\’ll do little to get me hired in a sociology department, it\’s difficult for me to understand how you think it would…but maybe you\’re right, that would be great, too!

on the other hand, i could write far fewer posts and take into account all the various literature and data that everyone else is professionally invested in. and that would be fine. some people do that. but usually i just want to get one intellectual link across (here, between smart parking and Robert Moses) in a short blog post. it isn\’t supposed to be and shouldn\’t be read as The Truth or a journal article, but instead spark some spin-off ideas by other people. like it did with this post. there\’s lots of good data in your comments, and i\’m happy people can read my post and your comments and have fun thinking through the issues. that\’s what public sociology is all about, and your post here only backs that up.

so thanks for the comments! i disagree with you that this conversation isn\’t public sociology or public intellectualism. also, you misspelled the name of my blog.

Hi Nathan, thanks for replying.

I don’t mean to say that The Society Pages or Cyborgology are *not* public sociology. Clearly they are in some ways, and I said TSP “espouses a certain form of public sociology”. There’s probably no way to sharply distinguish public from professional here anyway.

I was suggesting (after Burawoy) that the two dimensions may operate in tension — as suggested by the TSP mission statement wording — and that “public sociology” may be a difficult or elusive ideal, so it calls for self-examination of practices and context and motivation.

> on the other hand, i could write far fewer posts and take into account

> all the various literature and data that everyone else is professionally

invested in.

good point — it may be hard to know or follow what other fields consider essential, and be inhibiting to feel that one must. Although I find that Web research, e.g. starting with Wikipedia, seems to quickly uncover key reference points for a given topic. It might even be a productive strategy, in cases, to write something that engages and provokes for whatever reason, though not necessarily complete or rigorous, but which gets the Internet foot soldiers (the “cognitive surplus”) out to annotate it with the key sources and concepts the piece should know about. Either way the end result may have quality I often most value in writing, which is sense of mapping and orienting, pointing to essentials and patterns and key reference points.

> i assume it’ll do little to get me hired in a sociology department,

> it’s difficult for me to understand how you think it would

I was observing that the context of Cyborgology is The Society Pages, a project well connected into the Sociology academic profession, thus indirectly “accredited” in a sense. Tenure & Promotion criteria/practices is something I follow somewhat, because it’s integral to scholarly communication, and my picture is that while T&P these days is still often dominated by traditional measures such as publication in high Impact Factor journals or of monographs, it is gradually opening to recognition of other work, such as public

engagement or digital projects (e.g. in Digital Humanities).

The shift in or broadening of criteria is quite apparent with two movements I follow, “altmetrics”, and the UK higher-ed reforms around REF (Research Excellence Framework). The latter, facilitated by the former, is substantially foregrounding the criteria of public “impact” for evaluating and funding academics, and that impact is explicitly defined as, outside of academia.

In that context, it starts to be plausible that recognition within academia could come from, say, getting significant reader/viewership on The Society Pages, The Atlantic, or Huffington Post.

But we’re not there yet, as is suggested by your finding it “difficult to understand” how Cyborgology blogging would help you get hired in sociology. This underlines how professional and public sociology continue to be at odds, in the field’s T&P criteria.

> also, misspelled the name of my blog

whoops, sorry. I did know the spelling (in this case, significantly points to “cyborg” rather than just “cyber”) but some instances slipped past me. Corrected now!

thanks,

Tim

Pingback: Parking Wars, Public Soc, and Professional Thinkers » The Editors' Desk