- Why social media? public & professional engagement, better work

- Twitter, and other Open Interest-Graph Networks (OIGNs)

- Big Picture: Developing the Global Brain

- Twitter in Academia Now: early adopters & skeptics

- Problem: Who Has Time for This?

- Social Bridge 1, Autoregistration: your robot social secretary

- Social Bridge 2: Gateways

- Social Bridge 3, Autotweets: kick out the [academic] jams!

- Social Bridge 4, Auto-analytics: self-tuning and listening in

- Conclusion: There’s no ‘them’ out there, just a lot of ‘us’.

1. Why social media? public & professional engagement, better work

I admit: this might sound like the worst idea ever. Our harried guardians of truth, history, and scientific progress, called out to serve in the great Silicon Valley-born empire of the trivial.

But as Steven Johnson suggested in his 2009 Time cover story, “How Twitter Will Change the Way We Live,” social-media (in his case specifically Twitter), often strikes people as an awful idea at first.

The one thing you can say for certain about Twitter is that it makes a terrible first impression. You hear about this new service that lets you send 140-character updates to your “followers,” and you think, Why does the world need this, exactly? It’s not as if we were all sitting around scratching our heads and saying, “If only there were a technology that would allow me to alert my friends about my choice of breakfast cereal.”

[note: “what I had for breakfast” is an established convention to mean “trivial social-media content”].

However, Johnson goes on to recount the transformative experience of attending a conference at which Twitter use turned the event into a realtime, global, open conversation. The Twitter “backchannel“, as it’s sometimes called at conferences, provided instant summarization and discussion of all talks, available online as an ad-hoc “proceedings.” Connections were sparked among a spontaneously-gathered community of interest from around the world.

2. Twitter, and other Open Interest-Graph Networks (OIGN)

As Johnson’s story illustrates, a social-media system such as Twitter can, with the right circumstances and practices, facilitate and make visible an “interest graph”, or living record of who indicated interest in what and in what way (comment, endorse, purchase intent, etc). From seemingly simple/trivial means (140-character updates) there can be surprisingly rich and complex, emergent properties: threading together, democratizing, socializing, and accelerating discussion.

In Johnson’s 2012 book Where Good Ideas Come From: The Natural History of Innovation he argues that this type of online interaction is typical of the fluid recombination that leads to creative development across broad natural, social, and technological domains.

While Twitter is the best known example of this model, it isn’t the only one, and increasingly Twitter’s current management is reorienting the service towards a more traditional, one-to-many broadcast, ad-based media system. It may be that other networks, current or yet-unborn, will overtake Twitter in the connective/symmetrical interest-graph role — perhaps especially for particular communities such as academia generally or certain disciplines. New entrants such as Mendeley.com, Academia.edu, and App.net are possibilities.

Therefore, instead of “Twitter,” we might talk of Open Interest-Graph Networks, or OIGNs — like “Other” plus the German “Eigen” (“own, characteristic, proper”).

3. Big Picture: Developing the Global Brain

Let’s step back and consider this from above the above. Put away the “empire of the trivial” notion of social-media — which I know you arrived with — and let me suggest, instead, the idea of a global brain — a vast interconnected, adaptive web of cooperating scholars and researchers and perhaps enlightened humanity generally.

[The term “global brain,” incidentally, was coined in 1982 by Peter Russell in his book of that subtitle, but the concept is often traced back at least as far as Pierre Teilhard de Chardin‘s conception of the “noosphere”, around 1945].

[The term “global brain,” incidentally, was coined in 1982 by Peter Russell in his book of that subtitle, but the concept is often traced back at least as far as Pierre Teilhard de Chardin‘s conception of the “noosphere”, around 1945].

Not everybody, no doubt, would see incorporation into a global brain as a positive thing — you might see it as like the U.N. taking over world government times 10. But let’s set those issues aside and just focus on how we as global knowledge workers are going to rule! rule them ALL! at last! can move towards working more effectively and cooperatively to serve human goals.

Social media in this vision is not a place, or something like a party we ask harried academics to “come to” or “get on.” It’s more like an intelligent, adaptive, universal newswire whereby scholars and organizations, like neurons and areas of the brain, build up fine-tuned, live connections to receive and transmit stimuli (ideas, posts, papers, books).

Of course, the global knowledge or academic community has often been pictured this way, particularly since the rise of the Internet into broad use. However, here are some issues with the current global academic brain:

- It’s partially severed in many places: by non-engaging disciplines, inaccessible publications, nonpublic or nonreusable data, etc.

- It’s terribly slow at many key junctures: due to publication processes that may take monthes or years, glacial rate of change rate at university or department policies, etc.

- The “neurons” are not well-connected or bi-directional: academics have access to only certain channels of information, and often these aren’t efficient at conveying the desired stimuli. They often don’t know who’s working on the same stuff, who’s reading their stuff, or what’s most worth reading today. Researchers spend a lot of time searching and sorting and wading, to know what’s happening in just their increasingly narrow areas of specialization.

- This brain is often poorly connected to the body — that is, to the rest of society. Many nodes and neurons connect mainly among themselves, e.g. scientists producing work groomed for publication but not reproducible or usable; or humanistic disciplines retreating from public engagement, organizing around internal vocabularies and concerns.

The answer to all this, it turns out, is Twitter.

but I jest. No, of course Twitter, or the OIGNs to come, won’t solve all these issues. But they can help. They may partly build the connective tissue, the plasticity, the density of interconnection, the neurotransmitter vocabulary, and the elegance of design — which in massive combination brings us closer to a global mind.

back to top

5. Problem: Who Has Time for This?

Let me guess what you’re thinking. You’re thinking, this global brain sounds.. grand, really champion material. Meanwhile, could you please, for the love of all that is Holy, let me get back to work. This was just a bleeding smoke-break, mate, and you don’t even smoke.

Ok, Here’s the good news for you lab-shackled scientists, policy wonks, and secretive Renaissance scholars: we’re going to hook you up, in your current haunts, with your permission and at your speed, to help you out. You won’t have to crash the tawdry, vulgar, disreputable, embarrassing fraternity parties, sewing circles, or faculty receptions that you dread (or enjoy in secret) — the Facebooks, Pinterests, Diasporas of this trivial world.

Let’s just try to enhance and evolve what you already do — showing you who reads your stuff, telling you what the people you read find interesting. Now and then, we might bring round someone new at lunch, but it’s cool, you can chat or not. We’re on your team, the truth and knowledge-work team.

We have tools. We are team social and team future. Come with me if you want to live.

back to top

4. Twitter in Academia Now: Early Adopters & Skeptics

Scholarly metrics expert and “altmetrics” leader, Jason Priem, explored and quantitatively estimated scholarly Twitter use in his Nov 15, 2011 article on LSE Impact blog, “As scholars undertake a great migration to online publishing, altmetrics stands to provide an academic measurement of twitter and other online activity.” He considers Twitter a “revolutionary” form of scholarly communication that could transform centuries-old publishing practices into a much more efficient and organic “vast registry of intellectual transactions.” He suggests that while adoption is not yet high, it is only a 5-year old service, and it has strong interest and growth trajectory similar to that of early email:

Scholars are using Twitter as a scholarly medium, making announcements, linking to articles, even engaging in discussions about methods and literature. But….only about 1 in 40 scholars has an actively-updated Twitter account.

On Jan 11, Ernesto Priego of City University London, posted on Altmetric.com’s “Fieldwork” blog, “Fieldwork: Apples and Oranges? Online Mentions of Papers About the Humanities,” with results from an Altmetric.com study of 2012 data. and notes that the leading paper in the study was tweeted 61 times. He concludes that, while it is early days,

alt-metrics can be considered a powerful instrument to create awareness about the uses of social media to discover, discuss and promote research published online and the online audiences which are interested in this research

In an ensuing conversation on Twitter, Yves Winter (Political Science, University of Minnesota) argued that “in many fields (save media studies, digital scholarship, etc.) twitter impact = minimal,” and asked if “perhaps those of us who blog, tweet, etc. overestimate the efficacy of social media in academy?” Similar skepticism was voiced by Patrick Dunleavy, professor at London School of Economics and contributor to the LSE Impact of Social Sciences blog, who noted “Est. % of academics as yet on Twitter”, and commented “Interesting post on humanities and altmetrics – seems like small numbers & navel-gazing still tho.”

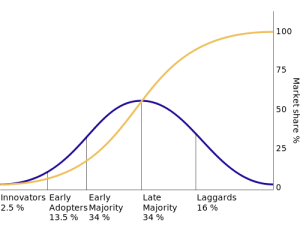

Acknowledging all those points, I would suggest the overall situation for scholarly social-media, particularly Twitter, is late stage of early-adoption, exhibiting arguments and positions characteristic of that phase. (it’s still not many people, what does it do for me? I have other priorities for my time, it’s low-quality and high-noise, my community doesn’t care about it, etc.).

However, there are various reasons to think social-media use will expand from early-adopter to “early majority” phase, in Everett Rogers‘ terms:

- in some areas it’s becoming a crucial medium for following conferences — both those you’re at in person, and those you’re not — and tracking current conversations.

. - social-media experience, even expertise is increasingly a job requirement,or at least differentiator, for new junior faculty hires in some disciplines, particularly humanities.

. - strong social-media skills are becoming key to developing the personal and learning networks needed for scholars to advance in a highly competitive profession.

. - Dissemination and discovery of research materials are increasingly mediated by social media, in the scholarly as on the wider Web.

. - The metrics for evaluating research quality are shifting towards usage and post-publication review, rather than journal Impact Factor or prestige, and social-media is a key vector to foster usage and positive reception of work.

. - Outreach and public impact is increasingly expected by departments, universities, and funders, e.g. under the REF evaluation system in the UK.

Nonetheless, early-adopter practices don’t necessarily or automatically turn into majority practices. Two key factors are

- diffusion by trusted peer channels (opinion leaders, change agents, connectors, who personally affect adopters), and

- increasing ease of implementation and confirmation (proof of value proposition).

A few things to note about this:

1) the dynamics are often non-linear, reflected in the steepening upward slope of the standard Diffusion Curve as early-adopter phase transitions to Majority. This typically reflects a “critical mass” effect, in which a practice flips to become necessary or assumed for peer relations. For example, when I started as an undergraduate, email adoption among students had been 5-10% for many years, mostly among computer-science and science studies; by my senior year, it had become 98%, and a campus paper had taken to printing the names of the holdouts monthly, as a mixture of mock-shaming the and warning others about which people needed special handling.

2) You have to consider who/what are key levers of peer influence in the population? For academics, this might be research collaborators, journals they contribute to or review for, or scholarly/learned societies they’re connected with. Even a bulletproof logical case for a practice is likely to have little effect if it comes from elsewhere.

3) Adoption accelerates as new tools/practices lower the barriers to entry and create faster paths to value demonstration. There are many types of barriers to entry, ranging from technical difficulty of using tools, lack of easily-available explanations and support, alienating cultural associations. Slow value confirmation is a form of barrier-to-entry, and particularly a problem with Twitter, because of its significant learning curve and low value before one has built a social/interest network there.

In the following sections, I’ll consider four possible ways to address these issues by lowering barriers to entry, value confirmation, and critical mass: Autoregistration, Gateways, Auto-tweeting, and Auto-analytics.

The basic idea: to make the party bigger, bring the party to the academics, not the academics to the party.

6. Social Bridge #1: Autoregistration – let your robot social secretary handle it

As it turns out, the research world has thought about the problem of trackable unique identity for scholars before. In his 2011 article “Google Scholar Citations, Researcher Profiles, and why we need an Open Bibliography,” ORCID director Martin Fenner reviewed existing schemes from Google, Research ID, Scopus, etc., and made a strong case for an independent, dedicated scholar identifier system, with mechanisms for user registration and updating.

While Google Scholar remains prominently apart, following its mass-scale algorithmic approach as opposed to ORCID’s social/community approach, it seems ORCID is well on its way to becoming standard infrastructure throughout other scholarly systems such as journals platforms.

Importantly, the integration of ORCID into other systems such as article submission is likely to make registration customary, expected of academics at key moment like paper submission.

Here’s the ORCID home screen, explaining how to register:

Here’s where the friendly, welcoming hand of social media can appear:

- ORCID could (perhaps has? discussed it earlier in 2012) add a Twitter account-name field in the ORCID record – and prompt user to enter it if they have one. (easy).

- If registrant doesn’t have a Twitter account, or doesn’t want to use it, offer to put them in a sign-up sequence, or autogenerate a Twitter account for them. It might be, for example, @orcid_[ORCID], where ORCID is their identifier number with leading zeros removed, currently 9 digits. This would, incidentally, make these ORCID accounts easily discoverable and trackable in Twitter.

- This Twitter (and/or other OIGN) account name could then be available in the ORCID registry for lookup by others, for social-media dissemination: for example, a journal tweeting a notice of accepting a paper by that author.

Of course you wouldn’t likely make any of this mandatory, but you could encourage it, make it easy to manage / turn off later, and provide good evidence of why it’s useful.

The main point is, ORCID to the academic is likely a quite trusted, important agent, which they are highly motivated to work with (for ensuring research credit, etc.), and which is in a position to do this on-boarding really well on a large scale.

7. Social Bridge #2: Gateways

Closely related to auto-registration is the idea of a gateway, or way to translate between social-media networks and other tools. Various exist already, and in Twitter has historically been an unusually cross-device, cross-media tool, designed from the start for seamless interoperation between SMS and Web. (you might say Twitter, initially, was almost nothing but a cross-system message gateway). .

But let’s consider some gateways which might be set up for academics:

1) Email to Tweet, and to get Tweets.

There are existing ways to email-to-tweet, if you have a Twitter account already.But let’s consider a way to offer this particularly for academic, non-early-adopters, building on the case of ORCID described above. Let’s say when you register (or get autoregistered) at ORCID, you’re offered a special email address — 314192405_twitter@orcid.org, say (the digits are someone’s ORCID, with leading zeros removed).

If you email to that address, it posts the first X characters to Twitter via the account you either registered with your ORCID or which was autogenerated for you. Likewise, if your Twitter account is mentioned or replied to on Twitter, that message would get emailed to you.

Side benefit: this might give you a way to communicate with friends and kids who don’t use email anymore.

2) Web submit

You might ask, what need, if you can just go to a Web form to sign up for Twitter account?

A) many people shy away from signing up for anything new, especially commercial services requiring email.

B) We might build Web forms/tools with useful augmentation services to make Tweeting easier and better. For example, here’s a tool I’m proposing for the PDFtribute project, to assist people in tweeting academic papers:

- enter a URL, title

- optionally, select discipline, other metadata fields, from pulldowns – they get added as hashtags

- Title gets shortened, key terms hashtagged

- conceivably, a DOI or other stable identifier assigned to post and added to tweet.

- when finished, you can either push button to have it tweeted for you, or copy and paste into your own Twitter tool.

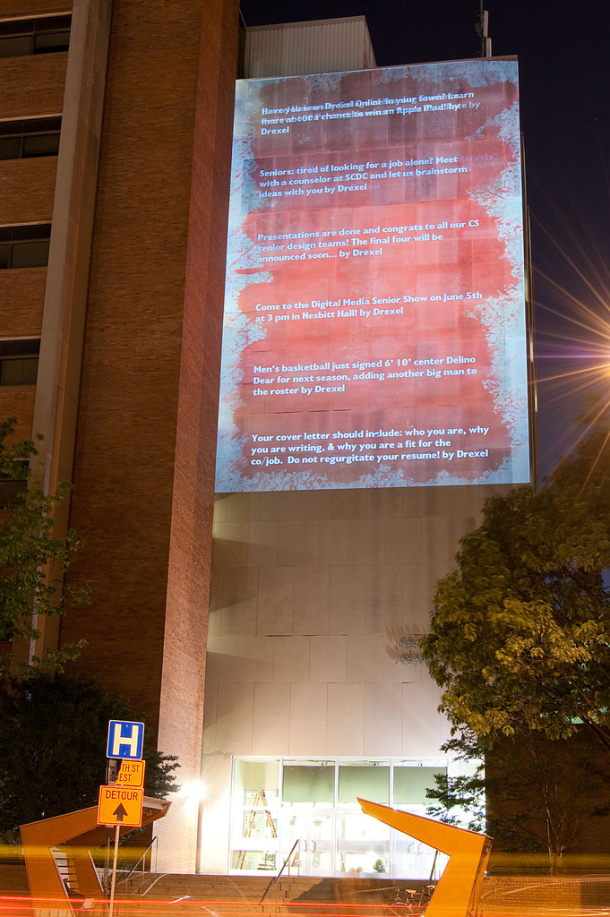

C) Wall displays

More fancifully, you could imagine academics or departments or universities adopting the “Tweet Wall” approach used at some conferences, in which wall-sized displays show real-time messages related to the event.

Perhaps enlightened faculties might create such Tweet walls projected on or from their buildings, up on the clouds even, showing what degree and topics of conversation they are generating.

I mean, if you’re aspiring to public scholarship, why go only half way?

8. Social Bridge #3: Autotweets – kick out the (scholarly) jams!

Related to the Tweet-generation form described above, we might have tools do such title extraction / keyword hashtagging, etc. automatically as part of a publishing flow on, say, large journal platforms. In other words, platforms like Elsevier, Wiley, PLOS, etc. could generate social-media messaging for all scholarly content on their systems, and let’s say Tweet upon publication.

Scholarly publishers are doing this in certain ways already, usually by having editors write tweets for certain promoted articles. However, this clearly doesn’t scale for large operations, and it doesn’t provide for systematic exploration of what writing, linking, hashtagging, etc. practices are most effective.

So, I bring you auto-tweeting! Which I believe, as Twain said about Wagner’s music, is better than it sounds. The idea often gets a negative reaction from people because it’s (obviously) dehumanized, couldn’t produce something with “voice”, etc. However, I would observe that this assumes that humans are to read the auto-tweet texts, when actually they may be more like transport mechanisms, delivering URLs that are automatically retrieved for human reading, meanwhile acting as a 2-way trace to note what is read, forwarded, favorited, etc. It’s like the brain: neurons aren’t that smart, but a lot of them woven together well and responding adaptively are smart.

Also, there’s an element of cyborg denial here, in that arguably we already use various prosthetics in tweeting, for example shortening links, scheduling tweets, letting Twitter filter our timelines, etc. Lowering the effort threshhold, to the point that various intentional gestures or workflow events may trigger tweets, can be a way to extend and network our intelligent activies, into a more “extended cognition.” Of course, this demands good filtering mechanisms on recipients side — for example via the structured subject hashtagging I described above in the PDFtribute tool idea, plus reading tools that easily allow keywork filtering / attenuation.

Lastly, it’s worth extrapolating from the auto-tweet tool to the intriguing but (to most) appalling case of autonomous Weavrs or Socialbots. As explored in the last few years by media experimentalists such as Philter Phactory in the UK and Tim Hwang / Pacific Social Architecting, SF, these software agents run on networks, following links and gathering data, following others and attempting to attract followers, engage in dialogues, generate narrative, etc. According to the Weavrs Tumblr, “Weavrs are wandering datasets woven from the conversational threads of the social web.” Wired.co.uk explores the phenomenon well in “Weavrs: the autonomous, tweeting blog-bots that feed on social content.” 28 March 2012.

Research-bots and Publish-bots

Although socialbot agents, as they stand now, are generally high-noise, conceptual explorations, they point to various productive possibilities.

For example, let’s imagine any given piece of academic research as forming some type of associational network of elements — citations, logical claims, allusions, identifiers. Then you can imagine a form of “publishing” consisting of a fleet of “publish-bots” which rove around looking for closely related conversations, then offering quotes, comments, associated links from the research. It may seem a little crazy, but consider that many academic-minded people do something similar all the time, when they think of and pass on quotes, citations, titles in response to a conversation or paper.

A “research-bot” is similar, except it seeks to gather rather than supply information. Weavrs.com has explored the concept of using Weavrs to interact with some environment such as a chat forum or urban streetscene and produce data for a visualization of it.

9. Social Bridge #4: Auto-analytics: self-tuning and listening in

Finally, we can (and are) thinking about various ways to reflect social-media activity back to academics in other places.

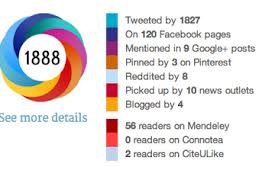

Well-known services providing this include Impact Story and Altmetric.com, the latter developed by Euan Adie at MacMillan’s Digital Science software incubator. (slogan: “Scientists talk. Let’s listen”).

Altmetric.com gathers data from many social networks and related services, and assigns values to different types of activity. This is aggregated into an “Altmetric score” for any given article, meant to be a proxy for the overall level of social-media impact that paper has had.

To me a perhaps even more interesting example of auto-analytics, or automatic social notation is illustrated by the Disqus commenting service. Like competitors IntenseDebate, Livefyre and Echo, Disqus offers a plug-in module to use on almost any web site, gives users easy single-sign on, and can pull together discussion from different sites.

The “automatic” aspect is that Disqus now monitors Twitter for URLs pointing to Disqus-equipped pages, and gathers/displays them on the page. This is illustrated in the screenshot below of one of my recent blog posts, on which all the tweets mentioning the post are automatically gathered. I was impressed by how easily I could set this up on my WordPress-based blog — it took just a few-minutes, 1-click install on my web-hosting company (Dreamhost). Also, I discovered that this tracks dissemination more broadly than Twitter itself does, since it (apparently) picks up anyone using the URL, not just retweets of my tweet or tweets by people I follow.

Something similar could be done on any online scholarly article page, or blog post, even faculty home page.

What’s powerful is that our unsociable academic can see all this activity, even go and check out his social-media fan base and their other comments, without ever having a Twitter account or having to admit to being “on Twitter.”

Therefore it directly creates a 2-way linkage to any web content via Twitter data-mining — well illustrating the concept of social media as organically-developing “connective tissue.”

So there you have four approaches for lowering social-media barrier-to-entry, reaching out to existing tools and non-early-adopters, and confirming value quickly:

- Autoregistration (e.g. on ORCID)

- Gateways (e.g. tweet-by-email)

- Auto-tweeting (e.g. from journal platform)

- Auto-analytics (easily see social-network activity and value signals around your work and reading.

In other words: bringing the party to you.

10. Conclusion: there’s no ‘them’ out there. It’s just a lot of ‘us.’

as humorist and Internet sage Douglas Adams said, in “How to Stop Worrying and Learn to Love the Internet,” (The Sunday Times,1999):

One of the most important things you learn from the internet is that there is no ‘them’ out there. It’s just an awful lot of ‘us’.

As we move forward, social media will feel less like an alien place that some other type of person goes to, and more like just one of the strands that link our lives together, like telephones or, as UC president Clark Kerr said, a common grievance over parking.

On other hand, it’s not necessary or likely for everyone to adopt the same practices — skills can be distributed among a community. This point is made indirectly in Douglas Adam’s “Learn to Love the Internet” essay, when he relates a description from Stephen Pinker on the generational difference between pidgin and creole languages.

A pidgin language arises when people who speak different languages cobble together a shared lingo. However, the next generation takes these fractured lumps of language and transforms them into something new, with a rich and organic grammar and vocabulary, which is what we call a Creole.

It may be that our stand-offish academics, declining the invitations to the social-media party, are quite sensibly seeing the current systems & practices as a sort of pidgin playpen, bits and pieces without a working grammar. Meanwhile, some of the most digitally-assimilated, social-media-embracing academics and knowledge workers are evolving Creole grammars of practice: in this case, the ability to work and thrive through newer, more “global brain” styles of hierarchy, synchronicity, attention, pattern recognition, and social behavior.

Or, to be less historically linear and totalizing about it, we might say that new types of creole storytellers and storytelling practices are emerging. Not everybody or everything will operate that way, but the new storytellers play a larger role in the society, and serve as connectors between others.

Lastly, There Will Be Cake

Let’s remember, we’re presumably good people, looking to get along and do good work, helped by new tools where useful.

Toadstool book forms. Image from Bethany Nowviskie presentation at MLA13, “Resistance in the Materials”

There will be cake — possibly a bit strange, mutant, cyborg cake, maybe made on a 3D printer or something? (toadstool book cakes, wtf?) — but still nice tasty cake. There will be books, articles, teachers, scholars, just woven together a bit differently. Come with us if you want to live.

Pingback: Social media | Pearltrees

Pingback: How To Bring Academics to the Social-Media Party? Indirectly | Tim … | Web Tech News

Pingback: Heteroglossia and Nonhominem for a More Civil Twitter | Tim McCormick

Pingback: Lectuur op zaterdag: een fictieve cursus, een lentecursus en een geflipte cursus. « X, Y of Einstein?

The unfortunate aspect of the blog is the lack of recognition of the risks inherent in social media engagement(although a somewhat deprecating option via Orchid might hint that there is some awareness on the part of the blogger) that those of us with intensive and many decade engagement in everything from early computer conferencing onwards are all too well aware of the price of unfettered Big Data moves by government the private sector and intelligence agencies – let alone retrospective health and insurance checks and exclusions, credit ratings and job fitness scans-, as institutinalised under the various banners of convenience of ‘anti terror’ ‘pedophilia’ ‘copyright violation’ and other scare flags.The strong moves to a unified single identity is simply a convenience for these parties. Consequently this ‘shy ‘ but highly digitally literate academic is to await a Tor or Silent Circle form of participation in social media…when many of these delightful concoctions will become accessibly to such digitally over literate academics…

Pingback: ‘Crossing the chasm’ with science social media | Tim McCormick

@jennifer_NYC @Protohedgehog my take on SM for acads: “How To Bring Academics to the Social-Media Party? Indirectly” http://t.co/87jyw6k0mZ

Great piece, especially from where it gets meaty about halfway down. I’ve been pushing Twitter wrapping (for want of a better phrase) at work to encourage non-geek engagement — you really fleshed that out (I’ll have this piece in mind next time it comes up) and chucked in lots of other ideas besides. Thanks for sharing :)

Pingback: Tim McCormick (@tmccormick)

Pingback: @lupicinio